Who's Protecting Us?

Want to take on the EPA? File it away here

Canton Repository

Monday, November 7, 2005

By PAUL E. KOSTYU Copley Columbus Bureau chief

COLUMBUS - Technology is catching up with the Environmental Review Appeals Commission. It bought new computers this year, replacing 1997 models. But not everything is high-tech or fast. When someone pays $70 to file an appeal of a decision by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Linda Adams writes the names of the parties in a ledger with binding that is held together with layers of tape.

Mary J. Oakley, the commission’s executive secretary, still operates from the same tan, steel desk she started with 33 years ago. The commission keeps no list of its former members. It had 16 employees at one time, but now it’s just Oakley and Adams, an office assistant for 12 years.

“It’s pathetic, absolutely absurd,” said Peter A. Precario, a former EPA lawyer and commission member now in private practice. “When I was there (from 1988 to 1992), they were still using a typewriter, typing 40-page documents through multiple versions.” The commission has little political power, he said, yet it handles a large number of cases in an “extremely important function. It’s an anomaly the way it works.”

NOT ENOUGH

Michael A. Cyphert, a Cleveland attorney who represents the construction and demolition debris landfill industry, said the commission is overwhelmed. “There are too many cases, and they take too long,” said Cyphert, who has argued before the commission since 1976. Because the commission has exclusive jurisdiction over all appeals on environmental matters, “it’s like one court taking every case in the state of Ohio,” Cyphert said. “They probably haven’t changed their rules and procedures for 20 or 25 years.”

Cyphert said the commission should operate like an appellate court, with multiple panels hearing cases. Instead, three commissioners hear every case. “There’s not enough money, and there’s not enough people,” he said. “They spread themselves very, very thin.”

“It’s the only place (people) can go,” said Richard Sahli, former chief legal counsel for the EPA and now a private attorney who argues cases at the commission. “If you don’t file it with ERAC, you don’t go anywhere else.”

IDEAL and real

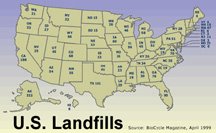

Here’s how the process is supposed to work: The EPA decides to issue a permit, say for a landfill expansion. Unhappy with that decision, opponents appeal, asking the commission to overturn it.

The commission holds a hearing, listens to witnesses and examines evidence. At least two members of the commission agree on an outcome and issue a decision. That can be appealed to a state appellate court and eventually the Ohio Supreme Court. Rarely, it goes to the federal court system.

But it doesn’t always work that way. In one case, the commission was so intent on backing the EPA that it issued a final order based on the decision of one member. An appeals court overturned the decision.

A former member of the commission, Jeff Cabot, said he doesn’t even think it’s the commission’s job to second-guess the EPA. He wrote in one case that it’s unreasonable to substitute “the commission’s judgment for that of the (EPA) director.”

OPEN MIND?

But during lengthy public hearings crammed with minutiae in a cramped room several blocks from the EPA’s offices, the commission is supposed to listen with an open mind. The process often takes months, sometimes years.

As of June 30, 470 cases were pending, some dating to 1991. Twenty-seven cases from Stark and Tuscarawas counties are pending; the oldest is an Ohio Power Co. appeal from 1996.

The commission also hears appeals of decisions by the state fire marshal, county boards of health, the state Emergency Response Commission and the Department of Agriculture. Those appeals, however, make up a small share of its total caseload. Most of the time, it is dealing with EPA decisions. And most of the time, it backs the agency.

Unless you are an attorney, the commission may not listen at all. According to commission rules, a citizen may present a case at a hearing, but only attorneys may speak for more than one person. And, though the hearings are a bit more flexible than those in a regular courtroom, it has rules. Citizens representing themselves are often overwhelmed and at a disadvantage when the EPA and companies send batteries of attorneys on their behalves. There’s no way to know how many people don’t bother to appeal an EPA decision because they can’t afford an attorney or the $70 fee.

Without an attorney to help argue their case, Ron and Pam Broering took on the Department of Agriculture and Ross-Medford Farms this year when they objected to the expansion of a hen-laying operation in Darke County from 183,000 chickens to nearly 1.28 million.

They lost.

Occasionally, the commission parts from the EPA. In one case, it told the EPA it lacked the authority to order an oil company to clean up a gasoline spill.

But usually, the commission rules in favor of the agency’s position and those aligned with it. Local health boards lose 68 percent of the time. Last month, for example, Waste Management of Ohio won a decision over the Cincinnati Board of Health, which has tried for four years to prevent the giant trash hauler from getting a license to operate a transfer station in the city.

“The test is whether the EPA director was reasonable and lawful,” Precario said.

A vast majority of the 4,511 cases appealed since 1972 are settled between the parties without a decision by the commission. The commission has decided less than one quarter of them, 989 cases. That’s not by accident, Precario said. “We provide as much opportunity and pressure to get the parties to talk and get the cases resolved,” Precario said.

Reach Copley Columbus Bureau Chief Paul E. Kostyu at (614) 222-8901 or e-mail: paul.kostyu@cantonrep.com

Rarely does Ohio’s Environmental Review Appeals Commission part with the Ohio EPA in its decisions, especially since the mid 1980s. In fact, at least one former member of the commission said it would be “unreasonable” to do so.

Name Years Served Appointed By ERAC Record

Christopher Jones 1999-2004 Taft 92.1%

Donald Schregardus 1991-98 Voinovich 85.2%

Richard Shank 1987-90 Celeste 71.2%

Warren Tyler 1985-87 Celeste 72.2%

Robert H. Maynard 1983-85 Celeste 93.5%

Wayne S. Nichols 1981-82 Rhodes 61.4%

James F. McAvoy 1979-81 Rhodes 37.6%

Ned. E. Williams 1975-78 Rhodes 55.1%

Ira L. Whitman 1972-74 Gilligan 42.4%

-- During the 33-year life of ERAC, the Ohio EPA director and those linked with the agency’s side of a case won 70.9 percent of the time.

-- There are 470 pending ERAC cases dating to 1991: 346 against Jones, 61 against Schregardus, and 44 since Jan. 1 against new EPA director John Koncelick.

-- More ERAC cases were filed against Jones or Schregardus than the five predecessors of Schregardus combined.

Source: Environmental Review Appeals Commission.

Canton Repository

Monday, November 7, 2005

By PAUL E. KOSTYU Copley Columbus Bureau chief

COLUMBUS - Technology is catching up with the Environmental Review Appeals Commission. It bought new computers this year, replacing 1997 models. But not everything is high-tech or fast. When someone pays $70 to file an appeal of a decision by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Linda Adams writes the names of the parties in a ledger with binding that is held together with layers of tape.

Mary J. Oakley, the commission’s executive secretary, still operates from the same tan, steel desk she started with 33 years ago. The commission keeps no list of its former members. It had 16 employees at one time, but now it’s just Oakley and Adams, an office assistant for 12 years.

“It’s pathetic, absolutely absurd,” said Peter A. Precario, a former EPA lawyer and commission member now in private practice. “When I was there (from 1988 to 1992), they were still using a typewriter, typing 40-page documents through multiple versions.” The commission has little political power, he said, yet it handles a large number of cases in an “extremely important function. It’s an anomaly the way it works.”

NOT ENOUGH

Michael A. Cyphert, a Cleveland attorney who represents the construction and demolition debris landfill industry, said the commission is overwhelmed. “There are too many cases, and they take too long,” said Cyphert, who has argued before the commission since 1976. Because the commission has exclusive jurisdiction over all appeals on environmental matters, “it’s like one court taking every case in the state of Ohio,” Cyphert said. “They probably haven’t changed their rules and procedures for 20 or 25 years.”

Cyphert said the commission should operate like an appellate court, with multiple panels hearing cases. Instead, three commissioners hear every case. “There’s not enough money, and there’s not enough people,” he said. “They spread themselves very, very thin.”

“It’s the only place (people) can go,” said Richard Sahli, former chief legal counsel for the EPA and now a private attorney who argues cases at the commission. “If you don’t file it with ERAC, you don’t go anywhere else.”

IDEAL and real

Here’s how the process is supposed to work: The EPA decides to issue a permit, say for a landfill expansion. Unhappy with that decision, opponents appeal, asking the commission to overturn it.

The commission holds a hearing, listens to witnesses and examines evidence. At least two members of the commission agree on an outcome and issue a decision. That can be appealed to a state appellate court and eventually the Ohio Supreme Court. Rarely, it goes to the federal court system.

But it doesn’t always work that way. In one case, the commission was so intent on backing the EPA that it issued a final order based on the decision of one member. An appeals court overturned the decision.

A former member of the commission, Jeff Cabot, said he doesn’t even think it’s the commission’s job to second-guess the EPA. He wrote in one case that it’s unreasonable to substitute “the commission’s judgment for that of the (EPA) director.”

OPEN MIND?

But during lengthy public hearings crammed with minutiae in a cramped room several blocks from the EPA’s offices, the commission is supposed to listen with an open mind. The process often takes months, sometimes years.

As of June 30, 470 cases were pending, some dating to 1991. Twenty-seven cases from Stark and Tuscarawas counties are pending; the oldest is an Ohio Power Co. appeal from 1996.

The commission also hears appeals of decisions by the state fire marshal, county boards of health, the state Emergency Response Commission and the Department of Agriculture. Those appeals, however, make up a small share of its total caseload. Most of the time, it is dealing with EPA decisions. And most of the time, it backs the agency.

Unless you are an attorney, the commission may not listen at all. According to commission rules, a citizen may present a case at a hearing, but only attorneys may speak for more than one person. And, though the hearings are a bit more flexible than those in a regular courtroom, it has rules. Citizens representing themselves are often overwhelmed and at a disadvantage when the EPA and companies send batteries of attorneys on their behalves. There’s no way to know how many people don’t bother to appeal an EPA decision because they can’t afford an attorney or the $70 fee.

Without an attorney to help argue their case, Ron and Pam Broering took on the Department of Agriculture and Ross-Medford Farms this year when they objected to the expansion of a hen-laying operation in Darke County from 183,000 chickens to nearly 1.28 million.

They lost.

Occasionally, the commission parts from the EPA. In one case, it told the EPA it lacked the authority to order an oil company to clean up a gasoline spill.

But usually, the commission rules in favor of the agency’s position and those aligned with it. Local health boards lose 68 percent of the time. Last month, for example, Waste Management of Ohio won a decision over the Cincinnati Board of Health, which has tried for four years to prevent the giant trash hauler from getting a license to operate a transfer station in the city.

“The test is whether the EPA director was reasonable and lawful,” Precario said.

A vast majority of the 4,511 cases appealed since 1972 are settled between the parties without a decision by the commission. The commission has decided less than one quarter of them, 989 cases. That’s not by accident, Precario said. “We provide as much opportunity and pressure to get the parties to talk and get the cases resolved,” Precario said.

Reach Copley Columbus Bureau Chief Paul E. Kostyu at (614) 222-8901 or e-mail: paul.kostyu@cantonrep.com

Rarely does Ohio’s Environmental Review Appeals Commission part with the Ohio EPA in its decisions, especially since the mid 1980s. In fact, at least one former member of the commission said it would be “unreasonable” to do so.

Name Years Served Appointed By ERAC Record

Christopher Jones 1999-2004 Taft 92.1%

Donald Schregardus 1991-98 Voinovich 85.2%

Richard Shank 1987-90 Celeste 71.2%

Warren Tyler 1985-87 Celeste 72.2%

Robert H. Maynard 1983-85 Celeste 93.5%

Wayne S. Nichols 1981-82 Rhodes 61.4%

James F. McAvoy 1979-81 Rhodes 37.6%

Ned. E. Williams 1975-78 Rhodes 55.1%

Ira L. Whitman 1972-74 Gilligan 42.4%

-- During the 33-year life of ERAC, the Ohio EPA director and those linked with the agency’s side of a case won 70.9 percent of the time.

-- There are 470 pending ERAC cases dating to 1991: 346 against Jones, 61 against Schregardus, and 44 since Jan. 1 against new EPA director John Koncelick.

-- More ERAC cases were filed against Jones or Schregardus than the five predecessors of Schregardus combined.

Source: Environmental Review Appeals Commission.

<< Home