Friday, November 11, 2005

Dangerous working conditions?

Countywide LF workers were located within a few feet of heavy equipment at the beginning of Club 3000's Nov. 10, 2005 inspection. One worker was wearing dark brown clothing which blended in with the dark brown truck while the enormous backhoe operated nearby. Another worker (wearing green vest and blue hooded sweatshirt) was kneeling next to the pit in close proximity to the heavy equipment (see bottom photo). Neither worker was wearing a hardhat during that portion of Club 3000's inspection.

Countywide LF workers were located within a few feet of heavy equipment at the beginning of Club 3000's Nov. 10, 2005 inspection. One worker was wearing dark brown clothing which blended in with the dark brown truck while the enormous backhoe operated nearby. Another worker (wearing green vest and blue hooded sweatshirt) was kneeling next to the pit in close proximity to the heavy equipment (see bottom photo). Neither worker was wearing a hardhat during that portion of Club 3000's inspection.

Countywide closed cell drainage

Taken Nov. 10, 2005, this photo shows the steep slope of a closed cell at Countywide Landfill, located in East Sparta (Pike Township), Ohio.

Taken Nov. 10, 2005, this photo shows the steep slope of a closed cell at Countywide Landfill, located in East Sparta (Pike Township), Ohio.Countywide LF is owned and operated by a subsidiary of Fort Lauderdale-based Republic Services, Inc.

.

Bills would extend moratorium on landfills

Friday, November 11, 2005

BY PAUL E. KOSTYU COPLEY COLUMBUS BUREAU CHIEF

COLUMBUS - Legislation by two Stark County lawmakers to stop landfills in Northeast Ohio, at least temporarily, has been introduced in both chambers of the Ohio Legislature.

State Rep. Scott Oelslager, R-North Canton, and state Sen. Kirk Schuring, R-Jackson Township, introduced companion bills Thursday.

Both bills would establish a moratorium on permits and licenses for new landfills and the expansion of current facilities in a 13-county area of the Tuscarawas River Basin. The moratorium would apply to both solid waste and construction, demolition debris facilities and remain in place for five years or until a study is completed by the U.S. Geological Survey, whichever is shorter.

The legislation also would allow solid waste management districts to pay for the study.

A six-month moratorium on the siting of new construction, demolition debris facilities and the expansion of existing facilities expires Dec. 31.

Meanwhile, a committee vote on another House bill that would revise the law governing construction and demolition dumps was delayed Wednesday until next week.

The bill, introduced by state Rep. John Hagan, R-Marlboro Township, is based on the final report of a study council created by the state’s biennial budget to look at regulation of the landfills. Hagan was on the council, which was chaired by state Rep. Thomas Collier, R-Mount Vernon. Collier also chairs the House Economic Development and Environment Committee, which is hearing Hagan’s bill.

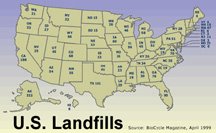

Northeast Ohio has the greatest concentration of landfills in the country. Some of them sit over a massive aquifer the stretches across 13 counties, including Stark, Tuscarawas, Wayne and Holmes.

Schuring and Oelslager have been working on their bills since September. Schuring said then the area needs the study because the aquifer has a significant effect on commercial, municipal and residential water supplies.

The two lawmakers included the provision to allow solid waste management districts to pay for the U.S. Geological Survey study after the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency raised concerns that money received from tipping fees cannot by state law be used on water studies. The agency also questioned whether one district had the authority to pay for a survey that included areas outside its boundary and would consider sources of pollution other than landfills, including agricultural, commercial and industrial sites.

Reach Copley Columbus Bureau Chief Paul E. Kostyu at (614) 222-8901 or e-mail: paul.kostyu@cantonrep.com

American Landfill fined for taking hazardous waste

Thursday, November 10, 2005

SANDY TWP. - Unknowingly accepting hazardous waste in March and May will cost American Landfill a $5,000 fine, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency said Wednesday.

American Landfill agreed to the fine after the EPA found out in June that the landfill took in 40 cubic yards of waste containing the remnants of sludge that resulted from an electroplating process involving nickel. The so-called sludge “filter cake” is considered hazardous and isn’t allowed into solid waste landfills.

The agency said the City Plating in Cleveland plant had changed its manufacturing process without American Landfill’s knowledge.

American Landfill, which is owned by Waste Management, has to review and change, if needed, its program to keep hazardous waste out of the landfill, the EPA said.

EPA spokesman Mike Settles said that American Landfill has stopped taking waste from City Plating, and it would be too difficult to find and remove the waste.

“It’s safely in the confines of the landfill and doesn’t pose a risk to anyone or the environment,” said Jerry Ross, Waste Management district manager.

Landfill fined for accepting hazardous waste

Thursday, November 10, 2005

American Landfill Inc. has agreed to pay a $5,000 civil penalty as a settlement for accepting hazardous waste at its Waynesburg landfill.

In March and May 2005, the landfill at 7916 Chapel St. SE, unknowingly accepted and disposed of 40 cubic yards of hazardous wastewater treatment sludge filter cake. Hazardous waste is not allowed in municipal solid waste landfills.

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency discovered the problem in June 2005 when it inspected City Plating in Cleveland – the company generating the waste.

Jerry Ross, district manager of American Landfill, said Wednesday that his company did not accept anything that is dangerous to the community.

“I guess the situation is we did in fact accept a waste stream and that is in violation of state regulations,” Ross said. “Again, it’s not something dangerous to the community, it’s just something that came in and was unacceptable.”

Ross said the documentation that the landfill received did not match with the waste that was actually disposed.

The OEPA press release said that American Landfill was not aware that City Plating changed its electroplating process prior to the problem being discovered by the OEPA.

Due to the elapsed time and the physical state of the filter cake, the landfill was unable to locate and remove the 40 cubic yards of disposed hazardous waste.

American Landfill no longer accepts waste from City Plating.

City Plating was cited for failing to manage and properly dispose of hazardous waste. In addition, the Stark County Health Department, the primary landfill enforcement agency in the county and the OEPA cited American landfill for accepting and disposing of the waste.

American will pay $5,000 to OEPA’s environmental protection remediation fund. To prevent future occurrences of this kind., American also will evaluate and revise the landfill’s hazardous waste prevention and detection program.

The company’s revised program will be submitted to the OEPA for review and comment.

No new landfills, legislation promises

Wednesday, November 9, 2005

By PAUL M. KRAWZAK Copley Washington correspondent

WASHINGTON - Rep. Ralph Regula was not deterred in May when a federal judge struck down his legislation blocking development of two area landfills.

Instead, the Bethlehem Township Republican rewrote the legislation in an effort to overcome the judge’s objections, and the full House might consider it as early as today.

Regula’s original ban, which dates to 2003, prohibited the Army Corps of Engineers from reviewing proposals to build the Ridge Landfill south of Wilmot in Tuscarawas County and the Indian Run Landfill northwest of Waynesburg in Stark County. Rep. Bob Ney, R-Heath, also has supported the ban.

The new ban, in the form of a rider to a spending bill, would block the Army Corps from reviewing applications for any new landfills in an 18-county area including Stark, Tuscarawas and Carroll counties. Expansions to existing landfills are exempt from the proposed ban. The prohibition needs approval from the House and Senate and President Bush’s signature to take effect.

Regula, a leading member of the powerful House Appropriations Committee, opposes any new landfills in or near his congressional district, which stretches from Stark County west through Medina, Wayne and Ashland counties. Contending the area already has enough landfills, he argues that any new ones would pose a threat to groundwater supplies used by the local population.

Norton Construction Co. of Independence, developer of Ridge Landfill, filed suit against the Regula-initiated ban two years ago.

U.S. District Court Judge Patricia A. Gaughan ruled in May that the prohibition was unconstitutional because it improperly singled out a specific developer “and prohibited it from having its application processed according to the same standards and procedures governing other applicants.” Proposed landfills require approval from both the corps and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency.

Gaughan further ruled there was no basis for prohibiting the development of the Ridge Landfill “in the name of protecting the region’s natural resources, but not extending this limitation with regard to any other landfills or landfill operators in that region.”

The re-crafted ban prohibits the Army Corps from reviewing proposed landfills anywhere in the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District, which is spread over 18 counties in eastern Ohio. If approved by Congress, the prohibition would be permanent until repealed or modified by lawmakers.

The future of the Ridge Landfill is still in litigation, since the corps appealed the District Court decision to the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. Last week, the appeals court put a hold on the corps’ review of the landfill until the court rules on the case next year.

Norton Construction did not return a phone call seeking comment on the rewritten ban. A U.S. Justice Department attorney, who has represented the corps in this lawsuit, was unsure what legal action the corps might take if the ban becomes law.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Ohio Senator Tom Niehaus on C&D LF debris

|

COLUMBUS "One man's trash is another man's treasure." While that saying is normally used in reference to unwanted items being discarded by one individual and sought by another, it describes the ongoing battle between construction and demolition debris landfill operators and some of their proposed neighbors.

One of the latest sagas in this perennial battle is playing out in the Ohio House now, and it will be coming to the Senate committee I chair, Environment and Natural Resources, in a few weeks.

The budget bill passed earlier this year created the Construction and Demolition Debris Task Force, and required members to conduct hearings and submit a report to the legislature by September 30. That same bill included a moratorium on issuing new operating licenses for what are commonly called C&DD facilities between July 1 and December 31 The expiration of that moratorium is driving the initiative to adopt new rules.

C&DD landfills accept the waste material from new construction, remodeling and demolition projects. They cannot accept solid waste. The regulations governing solid waste, the material you put in your garbage cans at home, are more stringent than those for construction debris. Solid waste has more potential for harm to the environment than most construction debris.

As a member of the C&DD Task Force, I participated in the August and September meetings. The committee issued its report, and while there was agreement on many points, some issues remained problematic. Those remaining issues have been the focus of legislative hearings in the House and at least one marathon interested parties meeting.

The most contentious issue is the location of these landfills. Opponents do not want them in their backyards. Others want C&DD landfills to follow the tougher regulations governing solid waste landfills. One problem with that proposal is the C&DD waste will use up more of our dwindling solid waste disposal space.

In addition, if C&DD facilities must meet the solid waste regulations, they might as well accept solid waste, and these same opponents who do not want construction debris in their neighborhood are even less likely to want solid waste.

If the legislature does not act before December 31, the moratorium will expire and C&DD facilities will be free to operate under existing laws. The task force recommended tougher regulations, including greater setback distances from homes, and the House committee is rushing to pass HB 397 so those recommendations become law when the moratorium expires.

The Senate will have limited time for debate if we are to meet the Dec. 31 deadline, so I have taken the unusual step of participating in the House discussions. My goal is to be thoroughly familiar with the proposal so when it comes to my committee I am familiar and comfortable with its contents.

Last Wednesday the House heard various witnesses testify for three hours about the proposed changes. I then joined the chairman and one member of the committee and almost 40 interested parties at what turned out to be a marathon seven-hour interested parties meeting that did not break up until close to midnight.

The group agreed on a proposal, and sent the legislation back to be rewritten. An electronic version was made available for everyone to review over the weekend. The House committee will meet again this week to ensure the bill says what those involved agreed it would say.

Regardless of the outcome, it is certain everyone will not be completely happy with the results. Disposal of CC&D or solid waste is always contentious.

To contact Senator Tom Niehaus call (614) 466-8082, e-mail him at tniehaus@ mailr.sen.state.oh.us, or write to him at the Ohio Senate, Room 38, Statehouse, Columbus, OH 43215. Please include your home telephone number.

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Ohio EPA Process Not Easy

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency makes many important rulings about how Ohioans, particularly Stark County-area Ohioans, are going to live their lives. And evidence points to citizens having too little say in the matter, specifically little chance to challenge the EPA bureaucracy.

That’s because all appeals of EPA rulings go through one small, old-fashioned, overworked office in Columbus, the Environmental Review Appeals Commission. It operates under rules that frustrate citizens who come together to challenge the state bureaucracy. Individual citizens cannot represent more than themselves. They must hire an attorney to come together and speak as one. There may be several purposes for this rule. One clearly is to keep citizens from coming together to pursue their common interests.

This commission also overwhelmingly sides with the EPA, which can’t really mean that the men whom governors have named as EPA directors are nearly infallible. Rather, the review commission defers to the EPA’s interpretation of environmental rules. As one critic of the system told Paul Kostyu, Columbus bureau chief for Copley Ohio Newspapers, 90 percent of the evidence could say that the EPA director is wrong, “but as long as there is a fact established that would support him, (the commission) is supposed to defer. I call that the insane director test,” Sahl said.

We ask the Stark County delegation to the Ohio Legislature: Can’t Ohio do better by its citizens than this system?

Who's Protecting Us?

Canton Repository

Monday, November 7, 2005

By PAUL E. KOSTYU Copley Columbus Bureau chief

COLUMBUS - Technology is catching up with the Environmental Review Appeals Commission. It bought new computers this year, replacing 1997 models. But not everything is high-tech or fast. When someone pays $70 to file an appeal of a decision by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Linda Adams writes the names of the parties in a ledger with binding that is held together with layers of tape.

Mary J. Oakley, the commission’s executive secretary, still operates from the same tan, steel desk she started with 33 years ago. The commission keeps no list of its former members. It had 16 employees at one time, but now it’s just Oakley and Adams, an office assistant for 12 years.

“It’s pathetic, absolutely absurd,” said Peter A. Precario, a former EPA lawyer and commission member now in private practice. “When I was there (from 1988 to 1992), they were still using a typewriter, typing 40-page documents through multiple versions.” The commission has little political power, he said, yet it handles a large number of cases in an “extremely important function. It’s an anomaly the way it works.”

NOT ENOUGH

Michael A. Cyphert, a Cleveland attorney who represents the construction and demolition debris landfill industry, said the commission is overwhelmed. “There are too many cases, and they take too long,” said Cyphert, who has argued before the commission since 1976. Because the commission has exclusive jurisdiction over all appeals on environmental matters, “it’s like one court taking every case in the state of Ohio,” Cyphert said. “They probably haven’t changed their rules and procedures for 20 or 25 years.”

Cyphert said the commission should operate like an appellate court, with multiple panels hearing cases. Instead, three commissioners hear every case. “There’s not enough money, and there’s not enough people,” he said. “They spread themselves very, very thin.”

“It’s the only place (people) can go,” said Richard Sahli, former chief legal counsel for the EPA and now a private attorney who argues cases at the commission. “If you don’t file it with ERAC, you don’t go anywhere else.”

IDEAL and real

Here’s how the process is supposed to work: The EPA decides to issue a permit, say for a landfill expansion. Unhappy with that decision, opponents appeal, asking the commission to overturn it.

The commission holds a hearing, listens to witnesses and examines evidence. At least two members of the commission agree on an outcome and issue a decision. That can be appealed to a state appellate court and eventually the Ohio Supreme Court. Rarely, it goes to the federal court system.

But it doesn’t always work that way. In one case, the commission was so intent on backing the EPA that it issued a final order based on the decision of one member. An appeals court overturned the decision.

A former member of the commission, Jeff Cabot, said he doesn’t even think it’s the commission’s job to second-guess the EPA. He wrote in one case that it’s unreasonable to substitute “the commission’s judgment for that of the (EPA) director.”

OPEN MIND?

But during lengthy public hearings crammed with minutiae in a cramped room several blocks from the EPA’s offices, the commission is supposed to listen with an open mind. The process often takes months, sometimes years.

As of June 30, 470 cases were pending, some dating to 1991. Twenty-seven cases from Stark and Tuscarawas counties are pending; the oldest is an Ohio Power Co. appeal from 1996.

The commission also hears appeals of decisions by the state fire marshal, county boards of health, the state Emergency Response Commission and the Department of Agriculture. Those appeals, however, make up a small share of its total caseload. Most of the time, it is dealing with EPA decisions. And most of the time, it backs the agency.

Unless you are an attorney, the commission may not listen at all. According to commission rules, a citizen may present a case at a hearing, but only attorneys may speak for more than one person. And, though the hearings are a bit more flexible than those in a regular courtroom, it has rules. Citizens representing themselves are often overwhelmed and at a disadvantage when the EPA and companies send batteries of attorneys on their behalves. There’s no way to know how many people don’t bother to appeal an EPA decision because they can’t afford an attorney or the $70 fee.

Without an attorney to help argue their case, Ron and Pam Broering took on the Department of Agriculture and Ross-Medford Farms this year when they objected to the expansion of a hen-laying operation in Darke County from 183,000 chickens to nearly 1.28 million.

They lost.

Occasionally, the commission parts from the EPA. In one case, it told the EPA it lacked the authority to order an oil company to clean up a gasoline spill.

But usually, the commission rules in favor of the agency’s position and those aligned with it. Local health boards lose 68 percent of the time. Last month, for example, Waste Management of Ohio won a decision over the Cincinnati Board of Health, which has tried for four years to prevent the giant trash hauler from getting a license to operate a transfer station in the city.

“The test is whether the EPA director was reasonable and lawful,” Precario said.

A vast majority of the 4,511 cases appealed since 1972 are settled between the parties without a decision by the commission. The commission has decided less than one quarter of them, 989 cases. That’s not by accident, Precario said. “We provide as much opportunity and pressure to get the parties to talk and get the cases resolved,” Precario said.

Reach Copley Columbus Bureau Chief Paul E. Kostyu at (614) 222-8901 or e-mail: paul.kostyu@cantonrep.com

Rarely does Ohio’s Environmental Review Appeals Commission part with the Ohio EPA in its decisions, especially since the mid 1980s. In fact, at least one former member of the commission said it would be “unreasonable” to do so.

Name Years Served Appointed By ERAC Record

Christopher Jones 1999-2004 Taft 92.1%

Donald Schregardus 1991-98 Voinovich 85.2%

Richard Shank 1987-90 Celeste 71.2%

Warren Tyler 1985-87 Celeste 72.2%

Robert H. Maynard 1983-85 Celeste 93.5%

Wayne S. Nichols 1981-82 Rhodes 61.4%

James F. McAvoy 1979-81 Rhodes 37.6%

Ned. E. Williams 1975-78 Rhodes 55.1%

Ira L. Whitman 1972-74 Gilligan 42.4%

-- During the 33-year life of ERAC, the Ohio EPA director and those linked with the agency’s side of a case won 70.9 percent of the time.

-- There are 470 pending ERAC cases dating to 1991: 346 against Jones, 61 against Schregardus, and 44 since Jan. 1 against new EPA director John Koncelick.

-- More ERAC cases were filed against Jones or Schregardus than the five predecessors of Schregardus combined.

Source: Environmental Review Appeals Commission.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Can't Fight Ohio EPA

By PAUL E. KOSTYU Copley Columbus Bureau chief

COLUMBUS - Got $70 to throw away?

File an environmental appeal.

Those who challenge a decision by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency will lose 92 percent of the time. You might as well throw the money into the landfill the EPA approved next door.

An analysis of 33 years’ worth of records by Copley Ohio Newspapers shows that individuals, corporations or consumer groups have little chance of successfully challenging the agency responsible for upholding the state’s environmental laws. For example:

Even as millions of flies swarmed into houses and cars and on to people, food and pets near the chicken warehouses run by Buckeye Egg in central Ohio, the EPA issued permits allowing the company to expand. Neighbors appealed. They lost.

-- When birds attracted to a county landfill posed a hazard to planes taking off and landing at a nearby small airport, the EPA said it lacked authority to help. The airport’s owners appealed. They lost.

Those unhappy with an EPA decision can file an appeal with the Environmental Review Appeals Commission, a three-member panel established in 1972 to act independently of the EPA.

But “in a battle between experts, the director wins,” said Richard Sahli, who was chief legal counsel for the EPA from 1987 to 1991.

By law, the commission “must affirm the director unless they find he acted unreasonably or unlawfully,” said Sahli, who now argues cases before the commission. He represents Club 3000, a citizens group fighting the expansion of Countywide Landfill in southern Stark County. He knows his chances of preventing the expansion are slim.

The commission must defer to the EPA’s interpretation of environmental rules. “So, 90 percent of the evidence could say the director’s wrong,” Sahli said, “but as long as there is a fact established that would support him, (the commission is) supposed to defer. I call that the insane director test.”

Sign of things right or wrong?

The odds don’t surprise Peter A. Precario, who was the EPA’s lawyer when the agency formed in 1972 and served on the commission for six years beginning in 1988.

Now in private practice, Precario represents the Village of Bolivar, which also is challenging the expansion of the Countywide Landfill. He said in the 1970s it made sense that a lot of the EPA’s decisions were overturned by the commission.

“At the beginning, there were a lot of unknowns,” he said. “We didn’t know from one day to the next what the hell we were doing. We were working with a body of regulations one day that would be scrapped four days later.”

Precario said the hundreds of early cases before the commission, then called the Environmental Board of Review, set precedent that the current commission follows.

Defenders of the EPA and the commission said the high rate of decisions in the agency’s favor means the EPA is doing its job right and there’s no reason to overturn its judgment.

“The system seems to work,” said Richard Shank, EPA director from 1987 to 1990 and now executive director of The Nature Conservancy — Ohio. “If the system is working right, the agency (EPA) should be making decisions that are clearly based on the existing law, and therefore the commission would basically have to uphold those decisions.”

“Some cases take two to four years to get through the Ohio EPA,” Precario said, “so it had better be doing it right. (The cases have) been gone over by dozens of experts. And it’s not like I agree with the EPA all the time.”

The EPA has a 76 percent success rate in the state’s appellate courts. Most of those appeals are handled by the 10th Appellate Court in Franklin County. Even when the commission rules against the EPA, the appellate courts often side with the EPA.

When the commission said a Cleveland suburb had an interest in a project affecting nearby wetlands, for example, the EPA appealed, and an appelate court sided with the EPA.

The EPA has a 71 percent success rate at the Ohio Supreme Court.

Six years to learn

Precario described the commission as conservative in its approach to the law, making it “a tough burden for those challenging an EPA decision.”

He said the cases the commission hears now are harder, technologically and legally, than those in its early days.

Most of the time, commission decisions are unanimous, though on a rare occasion a member will split with the majority.

By law, all three commission members cannot come from the same political party. Each serves a six-year term, which can be renewed. The appointments, made by the governor, are staggered every two years. One member must be an attorney and one must represent the “public interest,” which Precario said is defined broadly. But he said it’s difficult to imagine a commissioner not being an attorney because the cases are so dependent on understanding the law.

“It’s not a seat-of-the-pants operation,” he said.

If commissioners don’t have an understanding of environmental case law and precedent coming into the board, Precario said, they do by the end of a six-year term.

Reach Copley Columbus Bureau Chief Paul E. Kostyu at (614) 222-8901 or e-mail: paul.kostyu@cantonrep.com

For the record

Rarely does Ohio’s Environmental Review Appeals Commission part with the Ohio EPA in its decisions, especially since the mid 1980s. In fact, at least one former member of the commission said it would be “unreasonable” to do so.

Name Years Served Appointed By ERAC Record

Christopher Jones 1999-2004 Taft 92.1 %

Donald Schregardus 1991-98 Voinovich 85.2 %

Richard Shank 1987-90 Celeste 71.2%

Warren Tyler 1985-87 Celeste 72.2%

Robert H. Maynard 1983-85 Celeste 93.5%

Wayne S. Nichols 1981-82 Rhodes 61.4%

James F. McAvoy 1979-81 Rhodes 37.6%

Ned. E. Williams 1975-78 Rhodes 55.1%

Ira L. Whitman 1972-74 Gilligan 42.4%

-- During the 33-year life of ERAC, the Ohio EPA director and those linked with the agency’s side of a case won 70.9 percent of the time.

-- There are 470 pending ERAC cases dating to 1991: 346 against Jones, 61 against Schregardus, and 44 since Jan. 1 against new EPA director John Koncelick

-- More ERAC cases were filed against Jones or Schregardus than the five predecessors of Schregardus combined.

Source: Environmental Review Appeals Commission, as of June 30.

Canton Repository Nov, 6, 05 -Analysis proves you can’t fight the EPA

Canton Repository Nov 7, 05 - Who's protecting us? Want to take on the EPA? File it away here